Posted: May 17, 2021 at 8:16 am

We were lost on a two-lane road twenty kilometers from Aix-en-Provence when Devon said, “Dad, this boy back here is going to throw up.” This boy back here.

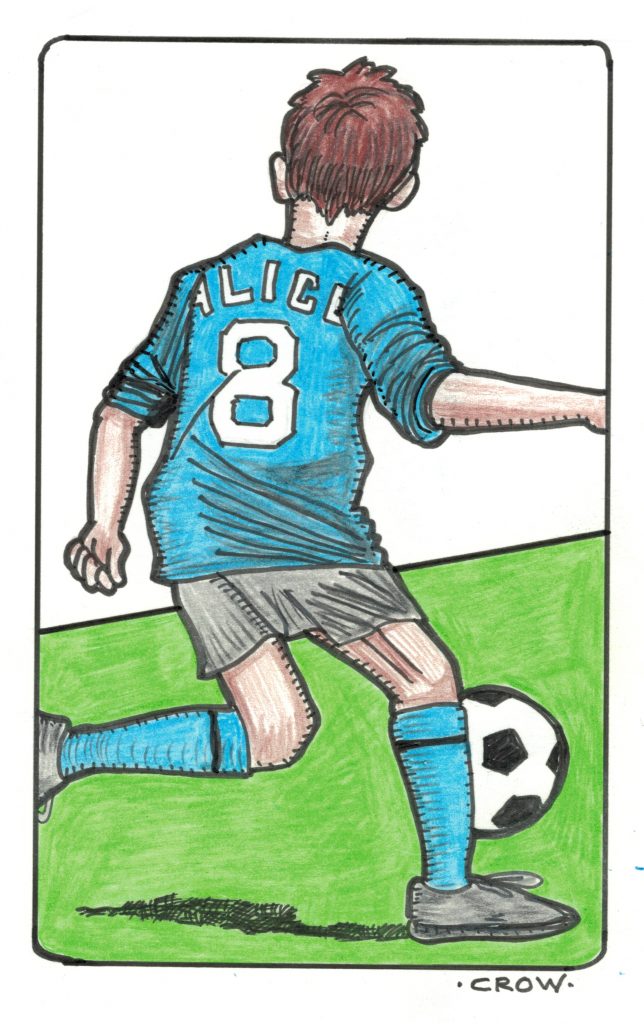

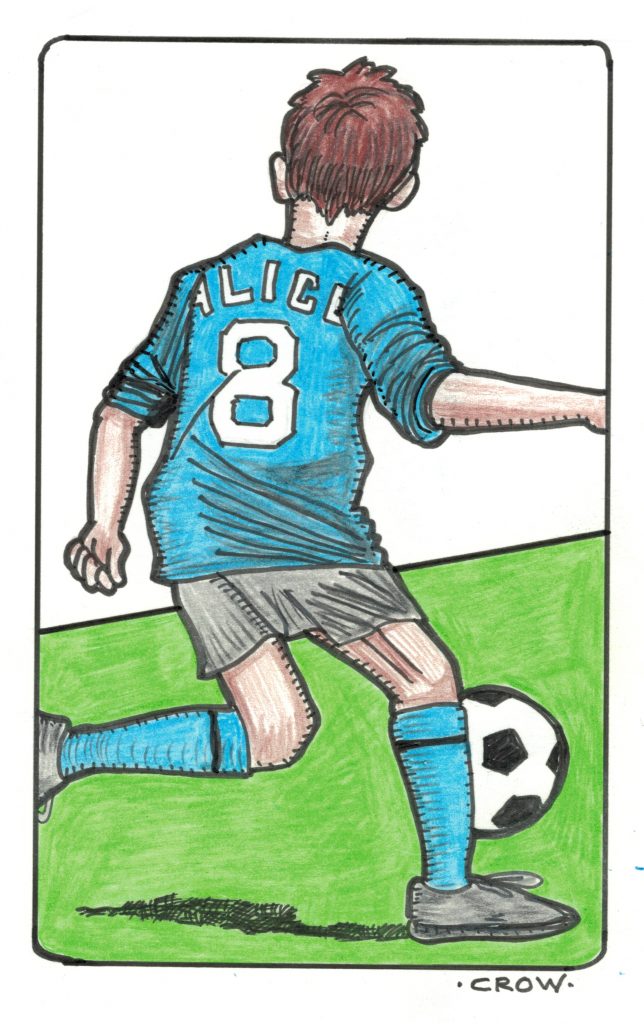

The Boy Named Alice, eight-years-old, had not spoken since he got in the car. A Marcel Marceau fan, he didn’t say he needed to vomit. He poked Devon and made throwing-up motions. I swerved my newish car to the shoulder and Carol pulled a plastic bag from her purse. Too late. A small dollop of puke made it into the bag. The rest splashed The Boy Named Alice, the backseat, the floorboards and the inside of the door. Neither Carol nor I are squeamish about vomit; we’re parents. But this was someone else’s kid, he seemed mute, and we didn’t know his real name.

“Kcchhhchhh,” said Sophie in the backseat, retching.

“Ghllghlhl,” said her brother beside her, holding his throat.

I scooped vomit from the upholstery with a Kleenex. Carol cleaned The Boy Named Alice’s soccer uniform, standing in the ditch. He remained silent, indifferent to the situation or the stranger scraping barf from his shorts. We left the putrid plastic bag and the vomit-slathered contents of a box of Kleenex in the ditch, to lie with the detritus common to the shoulders of French roads.

“I feel awful leaving our pukey garbage in the ditch, Billy,” said Carol. She looked down, and saw a spot of vomit on her shoe.

“I don’t like it either, but what choice do we have? I don’t know how much longer we’ll be stuck in the car.” I swallowed back something rising in my throat and gagged.

*

Every Saturday, Devon played a match for his Aix-based soccer club. The club employed a comical system to get players and parents to the out-of-town pitches each week. If I ran the club, I would send an email to each player’s parents on Monday, asking if their child could play that weekend. I would include the name of the hosting town and soccer field, the time to arrive there, and imbed in the note a Google map. A lawyer’s preparation. Call me crazy, but I imagine that would work out pretty well.

Devon’s club had a different system. On Thursdays I received a message from an anonymous texter, something like: “come to the stadium on Saturday at 2 p.m.” There was no information about the text’s author, the game time, the opponent, or whether the text had anything to do with my son or soccer. Was it an invitation from a Marseille wiseguy to pick up a suitcase of drugs? I felt like a Luddite, but an email would have been nice.

Being my father’s son, I had my family at the stadium five minutes early. That was my first mistake, forgetting about le petit quart d’heure (which allows every French citizen to be at least 15 minutes late for everything). Over the next thirty minutes, parents and players would drift into the parking lot. The first time this happened, I ignored the tardiness, and picked the least-late parent to befriend. I targeted a sallow-faced smoking father, held out my hand and said, in French, “Hello, I’m Bill, I’m Devon’s father.”

The man gave me one of those handshakes which offers only fingers, no palm. “Yes. Hello,” he said, without giving his name.

“We’re here from Canada. We’re living in Aix this year.”

“Yes. I know,” he said.

“Devon is enjoying playing for this club. Is this your son? What position does he play?”

“Oh, here and there.” The man tossed the remainder of his cigarette to the asphalt.

That was the end of the conversation. I made similar attempts to engage other parents on other Saturdays, but had the same results. With no parents to befriend, every Saturday we waited in silence for the latecomers, staring into the distance like models in department store catalogues.

Eventually, the coach told us the name of the town we had to find. I asked him the address of the soccer pitch. Every time the coach replied, “There’s only one stadium. It’s easy to find.” This was patently false.

The plan was each driver would follow the car in front, and we would arrive at the pitch en masse. Within thirty seconds, all the cars were separated. The soccer pitch was never plunked beside city hall in any of these towns, and was often outside the town’s borders and down an unmarked dirt road. One cannot find secreted and unnamed soccer pitches accessed by unmarked dirt roads without stopping several times to ask indifferent locals for directions. In French. With a Québécois accent. And we were late. Did I mention this scenario played out every week?

Well, not exactly like that every week – one Saturday had a vomitous twist. Sure, we had the mystery location, lack of directions, and chronic lateness. But as we were leaving our home stadium, the coach pulled me aside.

“Could you take another player in your car to Peynier?” he asked.

“Of course,” I said, as a uniformed boy peered up at me. It was his first game with Devon’s team, so I asked him his name.

The boy spoke to the asphalt. “Ah-leece.” What did he say?

I didn’t think it polite to ask him again since it was likely a normal French name I didn’t hear clearly. I let it slide.

“Do you usually play with a different club?” I asked the boy. He looked at me warily and whispered something to his father. They kissed each other on each cheek and the boy silently joined Devon in our car.

“Thank you for driving Ah-leece to the game,” said his father, strolling away.

His name couldn’t be “Ah-leece,” I thought, as “Ah-leece” was French for “Alice.” Was it an homage to Alice Cooper, or “A Boy Named Sue” knockoff? I decided to drive this kid to the match without knowing his name. As The Boy Named Alice’s father opened his car door, I thought, hold on, shouldn’t a parent know the name and number of the foreigner driving his son out of town? He didn’t even ask how he would collect his kid when, or if, we returned to Aix.

“Wait a minute, monsieur,” I said. “Shouldn’t we exchange phone numbers?”

“Yes. I guess so. If you want,” he replied, retracing his steps.

“Otherwise, how will you know when to pick him up?” Using a pronoun was a clever way to avoid saying the boy’s name.

“I was going to come back here in a few hours and wait for you,” he said.

Waiting, again. The French could plan better, but in France everyone waits for everything; it’s built into every process. This man was content to sit in a hot parking lot with only a vague idea of when a stranger might return his son sometime in the future.

“I think it’s better if I phone you when we’re close to Aix, and you can meet me here,” I said.

“OK, if you want to do it that way.”

Thirty minutes later, we climbed back into our car with The Boy Named Alice reeking of vomit, to continue our tour of Provençal roads which didn’t lead to the Peynier soccer pitch.

“I can’t sit beside this boy anymore,” said Sophie in English, to spare the feelings of The Boy Named Alice. “He stinks, and I threw up a little in my mouth.”

“Hang in there, Soph,” I said. “It’s rough, I know, but after a while you’ll get used to it. It’ll become our new normal.”

“Ewwww.”

We acclimatized to hurtling down the road in a metal box, the inside smeared with a thin film of puke. I was not surprised that once we reached Peynier, the soccer pitch was nowhere to be found. We approached a local man stuffing a mattress into a SmartCar, and I called to him before we were too close. I thought he would be reluctant to provide directions if he smelled our vomitorium.

“Excuse me, monsieur,” I said. “Do you know where the soccer pitch is?”

The man advanced toward the car in a friendly fashion, stopped abruptly and made a face like he had sucked a lemon. He reversed two steps and said, “I hope that’s a rental car. Heh heh. The soccer pitch, yes. Do you want the one beside the school or the new one that was recently built beside Monsieur Beaudrie’s estate?” He pulled a cigarette from where it was wedged atop his ear and flicked it to his lips.

“I was told there was only one soccer field. Could you give me directions to both? I have a feeling the game will be at the second field we drive to.” Prophetic.

Both sets of directions were unintelligible. We thanked the man with the sincerity he deserved, and drove away aimlessly.

“Dad, are we late?” asked Devon, drumming his fingers against the back of the driver’s seat.

“No, we’re not late.”

“Are we going to be late?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. It would help if there was a sign or something to tell us where the field is.”

“I’m getting worried. I can’t be late, daddy.” Devon’s finger-drumming intensified. “I hate being late for anything.” Like father like son, like grandfather like grandson, like great-grandfather like great-grandson.

We crisscrossed the town’s major streets, and chanced upon the school where the deserted soccer field was a stony, hardscrabble playground with rusted goals, the memory of nets blowing in the breeze. That couldn’t be it. We stopped an ancient woman shouldering a straw shopping basket with three baguettes sticking out.

“Excuse me, madame, but do you know where the soccer field is?” I asked.

“The soccer field?” she said with a screwed-up face, as if soccer was an obscure sport, like Quidditch or hockey. What we call “soccer” in Canada, and “football” in England, is “le foot” in France. When the French named their national sport, they chose an English word that none of them can pronounce. It sounds like ‘le fute.’ “There isn’t a fute field around here. The only field I know is down that way, about halfway to the next town.”

“Merci, madame.” This information would have been helpful when I asked the coach where in town we could find the pitch. Devon became increasingly agitated, and bounced his feet on the floorboards. The Boy Named Alice remained silent and unflappable. Scouring the roads between the two towns, we prepared to drive back to Aix when we passed a game of boules, bocce for you Italians. Like all games of French boules, the players were ancient, smoking men, with high-belted pants, ratty cardigans and cock-eyed cloth caps. A serious game for squinty-eyed competitors, mouths set in bloodless sneers. I was deathly afraid of interrupting this crowd with my stupid question in my stupid accent. But I love my kid, and he wanted to play soccer. I mentally prepared my question in French. And chickened out.

“Carol, I’m driving the car. You go ask them,” I said, looking out the window, away from her.

“No, Billy, you do it.” Carol crossed her arms. “You’re way better at French than me.” I hated when she said that. While true, her statement extracted her from making linguistic errors in front of car salesmen, immigration officials, doctors, the optometrist, the telephone company, the cleaning lady, the school board, the mayor’s office, and many people working in industries where knowing all the French words related to hockey (as I do) was useless. Carol spoke acceptable French, and was perfectly capable of asking directions. I exited the car to confront the boules players.

As I approached the group, the game immediately stopped. The players and spectators looked at me, not moving a muscle. Ten people standing still as stone, unsmiling.

“Hello, everyone,” I said. “I’m very sorry to interrupt your game. I’m trying to find the stadium near here. My son has a soccer game starting in a few minutes.” Blank looks all around. No one was happy I barged into their game.

“Where are you from?” asked an old woman with a kerchief tied to her head.

“Aix-en-Provence, madame.”

“No you’re not,” she replied. “If you were from around here, you’d know where our stadium is.” That witticism garnered laughs all around. “Americans,” the woman added, under her breath. More laughter.

“Well, we live in Aix now, but we’re from Vancouver. In Canada.”

A light switch was flipped somewhere as the woman broke into a bright smile and said, “Canada? Céline Dion? I absolutely love Céline Dion! You have a lovely accent just like her!”

I despaired for my country. Why did everyone in France equate Canada with Céline Dion? Couldn’t we do better than that? I felt it was an inopportune time to mention Céline Dion was my most intolerable public figure, music division, in the world. I had enough of her anguished theatrics when I lived in Québec City.

“You like Céline Dion?” I asked, faking enthusiasm. “We have the same birthday!” This was true, to my everlasting shame. My disgrace was almost cancelled out by the knowledge Vincent Van Gogh and Eric Clapton were in the same ignominious club.

“Lucky man,” she said, and gave me perfect instructions to a soccer pitch in the middle of a forest, covered by a Klingon cloaking device.

Once at the pitch, I was happy to see there was a bar.

After the game, The Boy Named Alice continued the silent treatment until we returned to our home stadium’s parking lot. The father of The Boy Named Alice was staring at the sky while sitting on a large rock, the kind put in parking lots to prevent French drivers from parking beside fire hydrants.

“Ah, there you are,” said the father of The Boy Named Alice, pushing up from the rock. “How did it go?”

“Fine, fine.” I said. “Well, there was a small problem. Your son was a bit carsick on the way there. He vomited a little in the car but he’s feeling better now.”

“Oh, I’m very sorry about that.” There was genuine concern in his voice. “Is your car okay? Can I do something?”

“No, it’s all cleaned up,” I said, shaking the hand of the father of The Boy Named Alice. “Don’t worry.”

As father and son wandered away, The Boy Named Alice said excitedly to his father, “……and we won our first game, but that team wasn’t too good, I was playing midfield, but in the second game, which we also won, they put me at striker and I scored two goals, the second goal was the best, I used the outside of my left foot so it was really hard…….”

It was considerate of The Boy Named Alice to let me know he could speak French. Sadly, his consideration had not extended to the previous three hours, when he could have said, “please pull over,” or “thanks for the ride,” or “sorry I puked all over your new car.” And the true name of The Boy Named Alice remains a mystery.