That evening, I sat in my favorite chair in la Pistache, the one beside the best reading light. I underlined incomprehensible phrases in La Provence in preparation for coffee with Cécile. The children watched The Adventures of Tintin on our tiny television.

“Daddy, can you help me with my homework?” asked Devon, five minutes before bedtime.

“Poor planning, Dev,” I said. “You’ve had all evening. Why are you doing it now?”

“I just remembered.” How could I be angry with him? I was a more skilled procrastinator in my youth. “I have some grammar and I have to review two pages of a story my teacher gave us.” I put down my newspaper.

“Let’s sit at the dining room table,” I said. I interrupted my reading with pleasure; I liked doing homework with my children more than, well, anything. They both had a curiosity about learning I found satisfying. They were also petrified of being unprepared for class, and wanted the highest score in any academic pursuit. There was no disputing these traits were paternal in origin.

“Dev, even though it’s late to start your homework, I love we have the time to do it together.”

“You always help me, daddy. Ever since I was a kid.”

“I appreciate that, Dev, but it’s not true. There were lots of times in Vancouver when I was working, or too cranky, and I couldn’t do this. In Aix I don’t have excuses. And you’re still a kid. You’re only in Grade Three.”

We started with grammar, my weakest subject. Devon delighted in correcting me, with sly grins of superiority. He often forgot I was the reason he was bilingual. At lesson’s end, I used the incorrect French verb for “to know.” The word “savoir” means “to know,” in the context of knowing how to do something. “Connaître” also means “to know,” but it’s used when referencing a person or a place, as in, “I know Paris well.” It’s easy to mix them up.

Devon looked like he swallowed a canary. “Dad, you can’t use connaître like that. You have to use savoir.”

“You’re only eight,” I said. “How can you know that?”

With a straight face, he said, “I don’t know, dad. I just savoir it.”

“Okay, enough grammar. What’s the story about?”

“Get it, dad? I savoir it.”

“It doesn’t get funnier the more you say it,” I said. “Tell me about the story.”

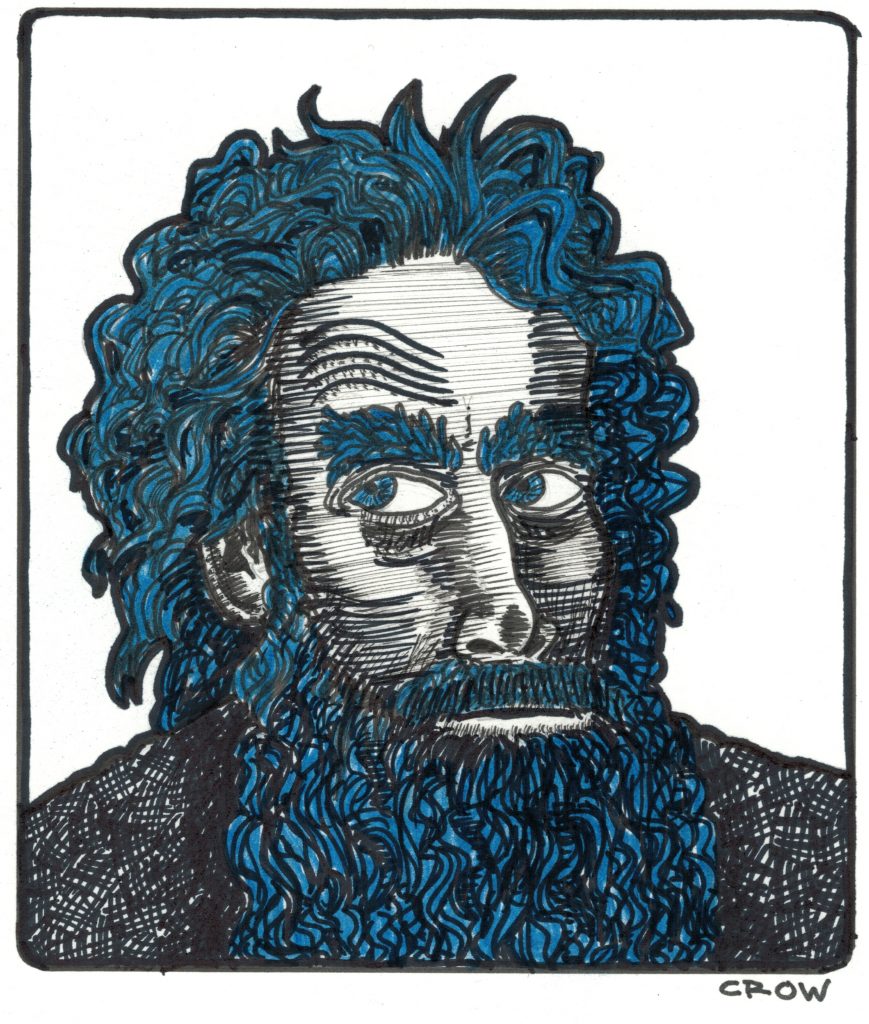

“It’s called ‘Barbe-Bleu.’ That means Bluebeard in English.”

“Thanks for the translation.” I knew this story, a well-known French folktale. We read it together, and I wondered what sadists chose the curriculum for eight-year-olds. The story is summarized as follows:

A wealthy man lived in the country. As a consequence of his unattractive blue beard, none of the local ladies would date him. His neighbor had two daughters, and Bluebeard asked to marry one. The daughters refused, citing Bluebeard’s ugliness, and the small issue of the disappearance of several of Bluebeard’s former wives. Bluebeard had some swinging parties, allowing the ladies to see he was a fun guy, and one daughter finally married him.

After a month of marriage, Bluebeard told his young wife he was taking a business trip. He gave her keys to the house, the safe, and the cabinets holding jewels and gold. He also gave her one tiny key, and made her promise not to use it to open the small door at the end of the hall. Of course, as soon as Bluebeard left, the wife entered the restricted room. It was covered in blood, and Bluebeard’s former wives, throats slit, hung from hooks (did I mention Devon was only eight?).

In a panic, the wife left the macabre scene and locked the door. Unlucky, she smeared blood on the tiny key, and being magic, it was impossible to clean. When Bluebeard returned, he demanded to see the keys, and asked his wife why the tiny key was covered with blood.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“You may not know,” said Bluebeard, “but I know all too well. You have gone into the little room! And now you will re-enter the room, and take your place among the others.”

The wife threw herself at Bluebeard’s feet, crying, and begged him…and begged him…and…

And that’s all we had of the story. Devon’s photocopy ended, mid-story, mid-sentence. He couldn’t read the ending, in which the wife was saved by her two brothers. They slew the serial-killer, rendering the widow both wealthy and Bluebeard-less. I worried about Devon going to bed with the image of Bluebeard’s many wives strung up on meathooks. As I tucked him into bed, he said, “Dad, you know what I was thinking about?”

Uh-oh, I thought. “Uhh, no. What?”

“You know what would be cool? In 1,000 years, people will look back and study us, like we’re prehistoric people. They’ll say, look, they actually reached down and used their hands to pick up a glass if they wanted a drink. Today, we have robot arms which bring the glass to our mouth.”

How am I going to give up these precious moments? I couldn’t go back to Vancouver and resume my regular job. I couldn’t be like I was before, I couldn’t miss out on my children’s ephemeral years, those unrecoverable years, being an absent father. I pinkie-swore with myself I would structure my new Vancouver life to allow for maximum family interaction, maximum mental engagement, Provence-level. I immediately regretted binding myself to the unbreakability of a pinkie-swear, despairing I could not construct such a life and still make a living.

I returned to my favorite chair with my laptop and a glass of rosé. “Just savoir it?” I had to record that story before I forgot it. I laughed out loud while typing. Why can’t my real life be like this? Crafting stories from the quirks of everyday living for my own amusement. Unfortunately, blogging wasn’t a career; my vignette would be thrown into the blogosphere’s yawning maw, where it would be read by fifty friends and be lost in the beast’s intestinal tract along with millions of blogs written by unfulfilled millennials.

That thought threw me down another well of depression, too deep to escape. While I was down there, I came to a woeful conclusion.